Press and Editorial

A heroic journey into abstraction

July 29, 2005Sebastian Smee

» View A heroic journey into abstraction exhibition

In John Updike's 2002 novel, Seek My Face, the main character, a painter loosely based on Jackson Pollock's wife, Lee Kasner, tells a young interviewer: "Someone of your generation probably can't believe how crucial, how important, how huge painting seemed then."

Referring to artists such as Robert Motherwell and Barnett Newman (lightly fictionalised as Roger Merebien and Bernie Nova), the painter goes on: "They all still spoke of painting in terms of self-exploration and an agonised authenticity that would revolutionise the world and whatnot, but the results

were a little like company logos, everybody working on the scale of 19th-century academic art but each of them having come up with some eye-catching simplification."

Updike comes across as admiring and sceptical about the achievements of the heroic generation of American abstract expressionists. But his character's deft analysis of the movement chimes with what several generations of art students, drilled in deconstruction and habitual myth-busting, have been taught to think about abstract expressionism.

Motherwell was a central part of that movement. He was one of the more convincing and original - and easily the most articulate - of the mid-century American artists who played such an important part in the shift of art's centre of gravity away from Paris to New York. Born in 1915, he was about a decade younger than Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Newman, and three years younger than Pollock.

He was set apart in other ways, too. After living and studying in France, he was more reluctant to disavow the influence of European modernism on the new American painting.

Unlike some of his peers, who were eager to present abstract expressionism as the artistic equivalent of a virgin birth, Motherwell was frank about the importance of artists such as Joan Miro and the French surrealists to the new movement. He once described modernist abstraction as an art "in the tradition of French symbolist poetry, which is to say an art that refuses to spell everything out. It's a kind of a shorthand, where a great deal is simply assumed."

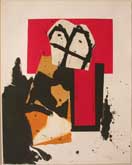

His experiments with collage acknowledge a heavy debt to pre-World War II European modernism. (Collage, he said, was "the greatest invention of modernism".) Many can be seen in a rare show of Motherwell's work at Sydney's Annandale Galleries, where price tags range between $17,800 for a

sketch and $277,000 for a painting.

Motherwell was not only extremely astute but also good at putting his ideas into words in ways that were free of much of the rhetoric and absolutism of people such as Newman and Rothko. His writings and lectures, published as a collection in 1992, have had an enormous influence on the way we think about

American post-war painting.

We know he was made uneasy by "action painting", the term introduced to describe painters such as Pollock by critic Harold Rosenberg in 1952. "It depends on what emphasis the word action is given," he told critic David Sylvester. "If it's given the emphasis that a painting is an activity - yes. If it's given the emphasis that it's like a cowboy with a six-shooter that goes bang, bang, bang, or is a gesture - then no."

He was eminently sane, then. Yet Motherwell was also a product of his time and no less caught up than anyone else of his age and sensibility in the idea that being an artist at that time - and specifically an American artist - involved a certain kind of heroism. This idea - especially as it applies to the abstract expressionists - has been pulled apart, caricatured and mocked in the intervening years to such an extent that one's iconoclastic bent loses sporting heart. So perhaps it is worth looking more closely at how Motherwell thought about it.

"The process of painting is a series of moral decisions about the aesthetic," he once said. This idea - that a decision about whether an area of paint was too lumpy and inert or whether a composition breathed

sufficiently could be essentially moral - was an extraordinary notion, not least because it makes the artist sound incredibly self-important.

But the morality of painting, for Motherwell, was not about piety and self-righteousness. Rather, it came down to what he described as "an animal thirst for something real". This resonated with what was going on in other areas of American culture, in the novels of Saul Bellow, the poetry of William Carlos Williams and the photography of Walker Evans, just for starters. In many ways, it has been missing from the art of our time, where all the stress falls on how artificial, how constructed everything is (although in the work of contemporary art stars such as Denmark's Olafur Eliasson and Italy's Vanessa Beecroft, a new awareness of reality beneath the oceans of artificiality and mass-mediation seems to be regaining currency.)

Motherwell was trained in philosophy and was inclined - similar to Eliasson - to analyse things and chew them over incessantly. But his thinking came straight out of the existentialist mould and when it came to his art he believed it was necessary to commit "one's own being and psyche and soul" without reservation.

He often spoke about the nature of this commitment in terms of the difference between the cultures of Europe and the US: "Tribal customs are less strong" in the US, he said. "That puts much more pressure on any given individual in relation to what his identity is going to be. He has to choose, alone."

In Updike's Seek My Face, the Krasner character confesses that, while married to the Pollock character, it had seemed to her "in my ignorance" that, in his painting, "there was too much groping and not enough finding". Now, more thoughtful and mature, she muses that "art has to fumble not to be decadent, it has to be just on the cusp of the possible, or we can't respond to it ... It has to be about us, just a skin away from being nothing."

Robert Motherwell: Paintings, Collages, Works on Paper and Board is at Annandale Galleries, Sydney, until August 20.

» View A heroic journey into abstraction exhibition

In John Updike's 2002 novel, Seek My Face, the main character, a painter loosely based on Jackson Pollock's wife, Lee Kasner, tells a young interviewer: "Someone of your generation probably can't believe how crucial, how important, how huge painting seemed then."

Referring to artists such as Robert Motherwell and Barnett Newman (lightly fictionalised as Roger Merebien and Bernie Nova), the painter goes on: "They all still spoke of painting in terms of self-exploration and an agonised authenticity that would revolutionise the world and whatnot, but the results

were a little like company logos, everybody working on the scale of 19th-century academic art but each of them having come up with some eye-catching simplification."

Updike comes across as admiring and sceptical about the achievements of the heroic generation of American abstract expressionists. But his character's deft analysis of the movement chimes with what several generations of art students, drilled in deconstruction and habitual myth-busting, have been taught to think about abstract expressionism.

Motherwell was a central part of that movement. He was one of the more convincing and original - and easily the most articulate - of the mid-century American artists who played such an important part in the shift of art's centre of gravity away from Paris to New York. Born in 1915, he was about a decade younger than Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Newman, and three years younger than Pollock.

He was set apart in other ways, too. After living and studying in France, he was more reluctant to disavow the influence of European modernism on the new American painting.

Unlike some of his peers, who were eager to present abstract expressionism as the artistic equivalent of a virgin birth, Motherwell was frank about the importance of artists such as Joan Miro and the French surrealists to the new movement. He once described modernist abstraction as an art "in the tradition of French symbolist poetry, which is to say an art that refuses to spell everything out. It's a kind of a shorthand, where a great deal is simply assumed."

His experiments with collage acknowledge a heavy debt to pre-World War II European modernism. (Collage, he said, was "the greatest invention of modernism".) Many can be seen in a rare show of Motherwell's work at Sydney's Annandale Galleries, where price tags range between $17,800 for a

sketch and $277,000 for a painting.

Motherwell was not only extremely astute but also good at putting his ideas into words in ways that were free of much of the rhetoric and absolutism of people such as Newman and Rothko. His writings and lectures, published as a collection in 1992, have had an enormous influence on the way we think about

American post-war painting.

We know he was made uneasy by "action painting", the term introduced to describe painters such as Pollock by critic Harold Rosenberg in 1952. "It depends on what emphasis the word action is given," he told critic David Sylvester. "If it's given the emphasis that a painting is an activity - yes. If it's given the emphasis that it's like a cowboy with a six-shooter that goes bang, bang, bang, or is a gesture - then no."

He was eminently sane, then. Yet Motherwell was also a product of his time and no less caught up than anyone else of his age and sensibility in the idea that being an artist at that time - and specifically an American artist - involved a certain kind of heroism. This idea - especially as it applies to the abstract expressionists - has been pulled apart, caricatured and mocked in the intervening years to such an extent that one's iconoclastic bent loses sporting heart. So perhaps it is worth looking more closely at how Motherwell thought about it.

"The process of painting is a series of moral decisions about the aesthetic," he once said. This idea - that a decision about whether an area of paint was too lumpy and inert or whether a composition breathed

sufficiently could be essentially moral - was an extraordinary notion, not least because it makes the artist sound incredibly self-important.

But the morality of painting, for Motherwell, was not about piety and self-righteousness. Rather, it came down to what he described as "an animal thirst for something real". This resonated with what was going on in other areas of American culture, in the novels of Saul Bellow, the poetry of William Carlos Williams and the photography of Walker Evans, just for starters. In many ways, it has been missing from the art of our time, where all the stress falls on how artificial, how constructed everything is (although in the work of contemporary art stars such as Denmark's Olafur Eliasson and Italy's Vanessa Beecroft, a new awareness of reality beneath the oceans of artificiality and mass-mediation seems to be regaining currency.)

Motherwell was trained in philosophy and was inclined - similar to Eliasson - to analyse things and chew them over incessantly. But his thinking came straight out of the existentialist mould and when it came to his art he believed it was necessary to commit "one's own being and psyche and soul" without reservation.

He often spoke about the nature of this commitment in terms of the difference between the cultures of Europe and the US: "Tribal customs are less strong" in the US, he said. "That puts much more pressure on any given individual in relation to what his identity is going to be. He has to choose, alone."

In Updike's Seek My Face, the Krasner character confesses that, while married to the Pollock character, it had seemed to her "in my ignorance" that, in his painting, "there was too much groping and not enough finding". Now, more thoughtful and mature, she muses that "art has to fumble not to be decadent, it has to be just on the cusp of the possible, or we can't respond to it ... It has to be about us, just a skin away from being nothing."

Robert Motherwell: Paintings, Collages, Works on Paper and Board is at Annandale Galleries, Sydney, until August 20.